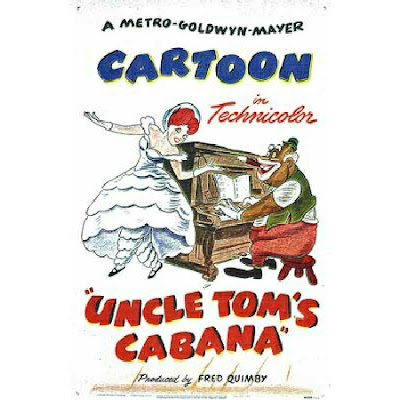

Uncle Tom seems quite...interested in Little Eva's dancing in the original theatrical movie poster...

Uncle Tom seems quite...interested in Little Eva's dancing in the original theatrical movie poster...(Thanks to puzzlesdirect.com)

Release Date: July 29, 1947

Director: Tex Avery

Music: Scott Bradley, Imogene Lynn (vocals)

In short: The story of "Uncle Tom's Cabin"--the way it "really" happened...

"One o' them Hollywood cartoon companies..."

With the fate of the "Censored 11" on this blog hanging in the balance for the time being, it's only appropriate to take a slight detour to 1940's Culver City, to take a look at a Tex Avery rarity from MGM.

Parodying a classic of literature as hoary as Uncle Tom's Cabin seems a bit dated even for 1947, and in the hands of anyone but Tex Avery, redundant--but for Tex, that was precisely the point. To him, the more ossified the source material, the better. He'd already mangled the fairy

tale--or Disney's re-invention of it, anyway--in such cartoons as CINDERELLA MEETS FELLA (with Egghead as the unlikeliest of Prince Charmings) and LITTLE RED WALKING HOOD at Warner's. At MGM, he gave audiences a Red Riding Hood the likes of which no one had ever seen, with a Wolf who still wanted to pursue her (to use the politest term possible) but for reasons decidedly not G-rated. The mawkish and melodramatic "Uncle Tom's Cabin" was just too good--or bad--to pass up. And with that story, he was treading on familiar territory.

He'd already taken aim at the story once before, for Leon Schlesinger (UNCLE TOM'S

BUNGALOW, 1937) but the maddeningly even pacing of the '30s Schlesinger cartoons made it something of a misfire. (Although he did give us the immortal line, "My body may belong to you, but my soul belongs to Warner Brothers!")

Ten years later, under the banner of a new studio, his comic timing sharper than it had ever been, the time couldn't have been better to revisit old material. Only this time, he makes a direct hit.

All the Avery trademarks are there: non-stop action punctuated by a jazzy Scott Bradley sound track, cuts so quick they pass by in an eye blink, visual hyperbole stretched to its most ridiculous--and funniest--limits. Not to mention a generous helping of sex, just barely slipped under the Hays Office radar. 1947 was a particularly good year for Avery--he released KING SIZE CANARY that year, generally considered to be his masterpiece. As with KING SIZE CANARY, UNCLE TOM'S CABAÑA starts slowly, but like a pebble rolling down a snow-covered hill, grows and gains momentum until it bowls the viewer over. We hardly have time to breathe by the time the film reaches its high point.

In the decade separating the two versions, the change in style and attitude coudn't be more obvious, especially toward the characters. Little Eva, portrayed as a chatty six-year-old in the Warner's version ("I'm in the first grade, an' I got a dolly, an' a teddy bear, and I can spell

"cat"--c-a-, c-a--well, anyway, I can spell "dog...") is no adorable little innocent here. She--like Avery's cartoons--had grown up, her little shoes filled by none other than Avery's "Red" from RED HOT RIDING HOOD, SWING SHIFT CINDERELLA and WILD AND WOOLFY. Albeit in more clothes than we had seen her in before, or since.

Save for the first fifteen seconds or so, the mythical Old South of the original story is nowhere to be seen--this was 1947, after all, so while Uncle Tom still has his cabin, it's in the middle of a towering urban landscape. Little Eva lives in the requisite antebellum mansion, but perched atop a New York-style skyscraper--her own little Tara-On-The-Hudson.

Simon Legree is still evil, so proud of his treachery he advertises it (signs on his downtown office building read "OLD LADIES TRIPPED, KITTENS DROWNED") but here he's also lecherous, proving an able stand-in for Avery's Wolf as he drools over Little Eva/Red. He and the Wolf could, in fact, make pretty good drinking buddies.

But before I get too far ahead of myself, let's visit UNCLE TOM'S CABIN--er, CABAÑA, as only Tex Avery could tell it:

We can see the opening titles superimposed over the traditional "Old South" background of mansions, cotton fields and steamboats--much like the opening seconds of the Bugs Bunny cartoon MISSISSIPPI HARE, but at night. The camera tracks over this landscape and zooms in on a lone little cabin in the midst of a vast field. Take a good look, should you get a copy of this, because that's just about the last connection to the original source material we're going to see in this cartoon.

Uncle Tom (here voiced by Charlie Correll, one half of AMOS 'N' ANDY) sits on the front porch of his cabin, surrounded by little black children lying on the ground in front of him. This "Uncle Tom" isn't quite the kindly, bowed old gent we're used to--in another, more subconscious connection to AMOS 'N' ANDY, he looks very much like an animated Andrew H. Brown, down to the big cigar, battered derby hat, and cocky attitude. Like more traditonal depictions of the "Uncle Tom" character, however, he has a fringe of white hair on the sides of his head and thick white eyebrows. He sits tilted back against the wall, and blows a bit of smoke from his cigar.

(Cut to medium shot). Picking up one of the children and putting him on his knee, he starts to tell his story, as Scott Bradley plays "Old Black Joe" on the soundtrack:

"Well now, chillun," he begins, "tonight ol' Uncle Tom's gonna tell you the real true story about 'Uncle Tom's Cabin...'" He absently flicks ashes from his cigar, seemingly on the child's head!

Uncle Tom turns his head from left to right as he addresses the off-camera children: "..Now, this is the first one o' them Hollywood cartoon companies ever got the straight dope on this Uncle Tom stuff. This is the way it really happened...once upon a time, in the big city..." (Fade to cityscape, presumably New York) ...live a character name Simon Le-gree." (Camera zooms in on office building, then fades to a shot of the entrance).

(V.O.:"He was sho 'nuff a scoundrel...") A marble sign above the door reads LEGREE BUILDING: LOANS, MORTGAGES AND CROOKED DEALS--on the left of the set of double doors, we see a sign proclaiming WIDOWS EVICTED, DOGS KICKED. On the right, it says OLD LADIES TRIPPED, KITTENS DROWNED. Etched into the walkway is a sign reading WELCOME SUCKER, in huge black letters. Refreshing to see truth in advertising for once...

The camera pans upward, then dissolves to Legree's office. We see Legree for the first time, in a black suit with tails--he has slicked hair, a waxed mustache, and even pointed ears--presumably to make him look more evil. Instead, he more closely resembles a cross between Bob Clampett's "Dishonest John" and an attendee at a Star Trek convention. (One anonymous poster to an online animation bulletin board I visited actually refers to him as "Dishonest John," apparently unable to distinguish between Avery's characters and Clampett's).

(V.O.:"That no-account crook was just rolling in dough...") If you know Avery cartoons at all, you know what's coming. Yep, money's strewn ankle-deep on the floor, and he leaps into the pile and rolls in it, as Bradley plays "Happy Days Are Here Again." Not only does money litter the floor, but one can see bags of it strewn randomly throughout the room, and on every available surface.

(Cut to medium shot of Legree, sifting coins through his fingers. V.O.: "And on top o' that, he was two-faced...") Right again--when we see him in profile, he literally has a face on each side of his head. For you Roman mythology buffs, something like the god Janus.

(Cut to medium shot of Legree, sifting coins through his fingers. V.O.: "And on top o' that, he was two-faced...") Right again--when we see him in profile, he literally has a face on each side of his head. For you Roman mythology buffs, something like the god Janus.(Cut to Legree walking camera left, full-figure. V.O: "But he sure was powerful...") Legree walks up on top of a desk, then back down to the floor, his legs lengthening and shortening

accordingly--like the "bridge gag" we saw in THE MAGIC PENCIL.)

(V.O: "Why, he done own that whole town--'cept for one little spot...") Legree continues walking screen left as the camera follows, then stops when he comes to a wall map, which shows one lone tiny square of land. He circles it with a pencil.

(Cut to close-up of circled area on map. V.O: "...And that was your Uncle Tom's cabin!")

(Dissolve to an impressive aerial shot of downtown, as the camera zooms down toward a tiny plot of land between two skyscrapers, with an equally tiny shack on it. Dissolve to Uncle Tom, tending his crops. V.O.: "I was sure happy...") Undoubtedly the most impressive scene in the picture-- nothing better illustrates to me the difference between cartoons of the Golden Age and today. Rarely will one see a camera angle so unusual in any of today's animated product, not even CGI.

(Cut back to Legree in his office, as he draws an "X" through Uncle Tom's property on the map).

(V.O: "But Mister Le-gree was figurin' on foreclosin' the mortgage on my cabin, so he could own the whole town.") Legree takes his incredibly broad-brimmed hat off a hook on the wall to his right, turns and puts the hat on his head--in a bit of exaggerated movement only Avery's unit could acomplish, for a moment it seems almost to stretch over his entire torso, then snaps back.

"He was sho' a low-down snake..." Uncle Tom continues. As if on cue, Legree's body stretches to become serpentine, as he slithers on the floor among his piles of money. The camera follows him to the left as he slithers out the door.

"He was sho' a low-down snake..." Uncle Tom continues. As if on cue, Legree's body stretches to become serpentine, as he slithers on the floor among his piles of money. The camera follows him to the left as he slithers out the door.(Legree slithers out into the hall, then stands as he comes to a door on the other side. V.O.: "Of course, the first thing he do is go for them bloodhounds...")

And of course, they literally are "blood" hounds--just after the camera cuts in closer to show Legree opening the door, it cuts again to show the dogs in hospital beds, hooked to IV's, pumping a rubber bulb with their paws. (A sign above them reads RED CROSS BLOOD BANK).

This

Thisindicates the cartoon, though released after World War II, had its genesis in the last days of the

war, as blood donations were highly encouraged then. Scott Bradley even accompanies the scene with a little bit of patriotic music ("Columbia, the Gem of the Ocean.") So much for my belief that Avery's last wartime gags were in JERKY TURKEY.

In an abrupt, instantaneous cut, we see the city in long shot, with Uncle Tom's tiny home among the towering buildings. A red helicopter lands in front of it. (V.O.: "So he come after me

personal...")

(Cut quickly to a view of Legree and Uncle Tom in medium shot. Legree gestures wildly, shakes his fist in the air, then literally sticks his nose in Uncle Tom's face, jabbing him in the chest with his finger. He mouths words, but we can hear no dialogue. Then again, we don't need to--he's obviously pretty irate. V.O.: ..."And he say that if I don't have the money by twelve o'clock tonight, he gonna take my little cabin...")

Legree pounds Uncle Tom on the head with his fist, squashing poor Uncle Tom's head down into his body as we hearthe last few words of the naration.

(Cut to the interior of the sparsely furnished cabin, where Uncle Tom sits dejectedly, his right arm slung over the back of the chair, his left elbow on a small table with a checkered tablecloth. He rests his head on his left hand. V.O.: "Oh, me--worry, worry..."). Scott Bradley, ever helpful, plays "Hearts and Flowers" on the sound track. (V.O.: "I didn't have a penny...")

Uncle Tom turns one of the pockets of his overalls inside out--not only is the inside of the pocket full of holes, but a swarm of moths fly out, illustrating his distressed financial state. (He casts a pathetic --yet somewhat funny--glance toward the audience.)

He turns and puts both elbows on the table as we hear the voice over: "And starvation was staring me in the face.." The camera pulls back to reveal a Grim Reaper-like figure across the table from him, reworking (or stealing) a gag used not only in the Woody Woodpecker cartoon PANTRY PANIC, but Norm McCabe's DAFFY'S SOUTHERN EXPOSURE for Warner's. But as with anything else Avery put his hand to, it comes off funnier in this cartoon.

Just above and behind the Grim Reaper figure, by the way, we can see a little shelf with a can on it, covered with cobwebs. More proof that poor Uncle Tom's in dire straits...

(V.O.: "But I got one last hope--my only friend, Little Eva..."). Uncle Tom walks slumped over to the right of the screen--the camera speeds past him in a patented Avery "jerk-pan" (see the

(V.O.: "But I got one last hope--my only friend, Little Eva..."). Uncle Tom walks slumped over to the right of the screen--the camera speeds past him in a patented Avery "jerk-pan" (see theJERKY TURKEY review from December '06). We see two phones--the small one on the left has a sign above it that says "Local", while the absurdly elongated one on the right says "Long

Distance"--another reworking of an earlier gag, this time from Avery's own RED HOT RIDING

HOOD (the short and tall cigarette girls selling "Regular" and "King Size" cigarettes.) Uncle Tom enters the frame and picks up the "Local" phone...

(Cut to an exterior view of a skyscraper as the camera pans up its endless stories. V.O.: "She

got this scrumptuous southern penthouse, you know...")

The camera continues upward until we see a long shot of Little Eva's home on top, looking like a piece of the GONE WITH THE WIND set grafted onto the Empire State Building: complete with magnolias, a fountain, and a columned portico.

(The camera zooms in, then cuts to the interior to show Little Eva, a.k.a. "Red," in her boudoir.)

She's wearing the expected anachronistic "southern belle" flowing dress. She picks up the receiver on her phone, which is sitting atop a little end table with a gauzy pink lace material around it. Her vanity table is just to her left. Uncle Tom, in voice over, adds the aside, "and that

ain't all she got, neither..." (Remember that statement, because I'll be coming back to it in my closing remarks).

(V.O: "She say she come right over...but we can't figure nothin' out.") During the narration, the scene wipe-dissolves to show Eva and Uncle Tom inside his cabin, with Tom seated in front of an upright piano. Little Eva stands next to it toward the left of the screen. Uncle Tom's dejected

(V.O: "She say she come right over...but we can't figure nothin' out.") During the narration, the scene wipe-dissolves to show Eva and Uncle Tom inside his cabin, with Tom seated in front of an upright piano. Little Eva stands next to it toward the left of the screen. Uncle Tom's dejectedexpression hasn't changed: he sits with his head cradled on one hand while he idly plunks a few keys with the other. Little Eva echoes Uncle Tom's body language, with the exception that she appears deep in thought.

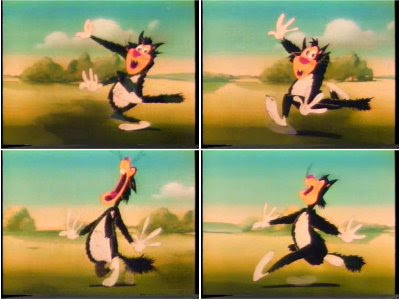

(V.O.: "Yeah, I was sittin' there, worryin', foolin' around with the pie-ano...") Uncle Tom stops pecking at the keys and launches into a lively boogie tune. Eva, getting into the spirit of the

moment, starts dancing. The camera follows her across the room as she continues her dance

(the cabin appears to be twice as large inside as it did originally, thanks to cartoon magic. She needed room to dance, so there it was). The camera pans back to Uncle Tom at the piano, his expression changed dramatically. He has an idea! ("When all of a sudden it come to me..." the

voice-over says.) His mouth is in a wide-open grin as he slams down hard on the keys. (V.O.:

..."the big idea!!")

The "big idea", as he tells us, is to open his little cabin to paying customers, remaking it into

The "big idea", as he tells us, is to open his little cabin to paying customers, remaking it into"Uncle Tom's Cabaña!" ("Yowsuh!"). He says in voice-over, "We done turned that cabin into a

nightclub--the place was packed!" We see an exterior shot of the transformed cabin at night, with a blinking neon sign proclaiming the establishment's name in lights--underneath, in smaller letters, are the words "Dining and Dancing." Cars pop up into newly-constructed parking lot from out of nowhere, multiplying in a pixilated sort of effect. Scott Bradley contributes a lively version of the "Tiger Rag" as the scene wipe-dissolves to show a poster of Little Eva: if you look closely--very closely--you can see a small blinking sign in the background that reads, "No Dogs Allowed...Wolves Welcome." (Good one, Tex. Too bad your Wolf didn't get an invitation. But as I've already mentioned, he had a more than worthy substitute).

Bear in mind, this is all in the space of a couple of hours, supposedly. Money can indeed work miracles, especially in a cartoon.

(V.O., as we cut to a scene of a dinner-jacketed Uncle Tom behind a counter, pulling in huge

piles of money and stuffing it into a cash register: "We was really coinin' [or was it "cornerin'] the dough!")

(The camera pans right. V.O.: "'Course, Uncle Sam was gettin' his share..." We literally see the

figure of an ecstatic Uncle Sam, as he rakes money into a bag marked TAX $$. Bradley, of

course plays "Yankee Doodle").

Cut to a shot of Legree looking at the nightclub through a telescope pointed out of his office window. (V.O:..."But Legree wasn't gettin' his...and he was gonna do somethin' about it!") He throws down his telescope disgustedly, turns and stomps off through the piles of money carpeting the floor. (Cut to Legree outside the window of the cabin, where he grabs himself by the seat of the pants and lifts himself up to sneak inside).

(V.O: "Next thing I know, he got me tied to that powder keg and lightin' the fuse..." We see the interior, with Uncle Tom tied to gigantic barrel of gunpowder about half the size of the room, while Legree holds the fuse. He lights it and zips out of frame to the right.)

(V.O: "Next thing I know, he got me tied to that powder keg and lightin' the fuse..." We see the interior, with Uncle Tom tied to gigantic barrel of gunpowder about half the size of the room, while Legree holds the fuse. He lights it and zips out of frame to the right.)Cut again--bear with me, this is an Avery cartoon--to a shot of Legree grabbing the cash register, hiding it under his cloak, and tiptoeing away. (V.O: "And he done take every penny of that money and get out of there...")

(V.O.: "But he done forgot somethin'...it was Little Eva.") Legree turns when he hears off-camera applause--the camera pans right to the stage, where Little Eva makes her entrance, carrying a parasol. (Cut to a shot of Little Eva as the camera zooms in closer).

(Cut back to Legree. The cash register he'd been carrying swells under his cloak as he looks

lustily off-camera. The cash register drawer bursts open, spilling its contents all around Legree.) I hadn't made the connection when I first saw this, but a fellow online reviewer happened to comment this was perhaps Avery's wildest erection gag to date. I have to admit he's right.

To the sound of a horse whinnying and galloping, Legree runs offscreen camera right--we cut to him atop a table where he stiffens into the pose of a hunting dog who's just spotted his prey. His head's flattened, making his pointed nose resemble an arrow, while the tail of his coat resembles a real "tail." Accompanied, of course, by a nice "boing!" on the soundtrack. Tex was anything but subtle.

(Cut to a medium shot of Little Eva, who looks somewhat disdainfully in Legree's direction.)

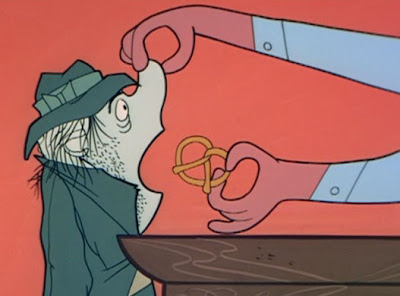

(Cut to a medium shot of Little Eva, who looks somewhat disdainfully in Legree's direction.)She starts to sing a slow, sweet rendition of "Carry Me Back To Old Virginny..." As she gets to the line "That's where the cotton and the corn and taters grow..." we cut back to Legree, who levitates up to the ceiling with a stupefied look on his face. We cut back to Eva as she sings the next line, then to Legree, who's attempting to pour salt on a stalk of celery. He's so entranced, though, that he gets a little mixed up--he shakes the celery and takes a big bite out of the salt shaker. He opens his mouth to reveal his teeth crumbling to pieces.

Suddenly, Eva tosses down her parasol and launches into a swing version of the song. Legree attempts to light a cigar, but instead lights his nose. Unfazed, he pulls a "Lucy Ricardo," merely removing his flaming nose and snuffing it out in the ashtray.

We make another couple of quick cuts from Eva back to Legree--this time, he's got a plateful of ham and several slices of bread on the table in front of him. Intending to make a sandwich, he instead butters his own hand, puts a slice of ham on it, places his other hand on top of that, and proceeds to munch on his own fingers all the way up to the elbows.

We make yet another couple of cuts from Eva back to Legree, who this time is trying to slice the pie in front of him. Instead, he takes an enormous pie-shaped slice out of the table and chomps on it.

Little Eva finishes her song with a flourish, kicking and flinging up her skirts, ending her number with by sliding on her knees to the edge of the stage. (A real testament to Preston Blair's animation abilities here--she was never quite this spirited in the other "Red" cartoons.)

(V.O.: "Wow! That done it!") Legree goes crazy with desire, smashing dishes over his head and for some reason known only to him, pours an entire bottle of ketchup on himself. He proceeds to pick up the table--now miraculously whole after Legree cut a chunk out of it--and slam it down on his head several times.

He runs up on stage toward Little Eva as we hear galloping noises on the soundtrack, only to race past her and grab a support beam. He breaks off a piece of it and starts to kiss it passionately, then runs off with it in the other direction. Realizing what he's just done, he stops, throws the beam down and disappears from frame, only to return a half-second later with the right quarry--Little Eva--this time. (V.O.: "Now he gon' get the gal...")

(V.O.: "That's what he thinks...") Cut to Legree running toward the door, only to find Uncle Tom waiting for him when he opens it. Uncle Tom clobbers Legree with a huge mallet (surprisingly few mallet hits here for an Avery cartoon) sending him through the floor. Legree's head pops up as the camera zooms in closer--it closely resembles a large tack.

Meanwhile, we return to the present, where Uncle Tom is still regaling the children with his story.

The child on his knee says, "But Uncle Tom, why wasn't you blown up on that powder keg?" (What happened to Little Eva, for that matter? Legree was still carrying her when he got clobbered.)

"Why, that was nothin'!" he says, waving his hand. "That sweat pourin' off me just naturally put that fuse out!" Before he finishes saying this, we cut back to a shot of him tied to the powder keg--he's sweating so profusely the liquid's halfway up the wall, soaking the fuse.

(Cut to a shot of Uncle Tom, on the left of the screen, with Legree on the right. V.O.: "Then

Legree came at me with that machine gun..." The bullets, surprisingly, bounce harmlessly off him as he stands in the doorway with a hand on one hip).

Midway through the shooting, the listening child interrupts, and we cut abruptly back to the present. "But Uncle Tom," the child says. "Didn't dem bullets kill ya?"

"Why, of couse not boy..." Uncle Tom says. He flicks the ashes off his cigar and we fade to black

"Why, of couse not boy..." Uncle Tom says. He flicks the ashes off his cigar and we fade to blackfor a second. We then dissolve back to Uncle Tom standing in the doorway of his cabin, bullets still flying off him. "I had on my 'Superduperman' suit!" He opens his shirt to reveal red flannel long johns with a large "S" imprinted on them, as the bullets continue to bounce off harmlessly.

We make another quick cut (V.O.:"Then he tie me on them railroad tracks, and the train run over me!") Then another (V.O.: "Then he throw me in that sawmill!"). Here we see Legree pulling the lever to operate the huge buzz saw, which literally saws Uncle Tom in half. The train sequence is especially good here, if only for his grimace as the train literally runs over him.

--"but Uncle Tom," the child interjects as we cut back to his front porch. Uncle Tom scowls at the interruption. "Don't bother me now, boy, I'se really goin'!" (My second-favorite line in the picture, in case you were wondering. My favorite? You'll soon find out).

He resumes his story, which builds to its ridiculous climax with a series of cuts no longer than about three seconds each. He says, "Then he shove me off that cliff...then I jump on that camel...then he chase me with that elephant...then he throw me to that alligator..and here come that steamroller...and that P.T. boat..."

The sequences accompanying the above are textbook pieces of classic animation, worthy of study by contemporary film students. We see:

a) Legree on the cliff, in extreme long shot, at the very top of the screen, as he tosses Uncle Tom over...

b) a long shot of the two of them running through the North African desert on camels that resemble dromedary versions of the horses from WILD AND WOOLFY: spindly, knobby legs with huge feet, narrow, almost pinpoint heads and huge snouts. Legree pounds Uncle Tom with a mallet that frankly, would be too heavy for him to lift in the real world--it's twice as big as he is. There's some classic "squash and stretch" on Tom as he flattens and straightens out with every blow, while Legree seems suspended in midair as he clobbers Tom.

c) Legree standing on a goofy-looking elephant at full gallop--the elephant has a body like a gray

c) Legree standing on a goofy-looking elephant at full gallop--the elephant has a body like a graybeach ball, and feet that look too small to support it. Legree sends an unbelievable hail of bullets

down on Uncle Tom.

d) Uncle Tom being thrown right into the mouth of an enormous alligator, which seems about three times as big as any actually on Earth...he literally rolls down the creature's throat, and the beast's enormous mouth snaps shut like a living valise--perhaps the only instance in which a person being eaten alive seems funny.

e) A steamroller which takes up most of the frame, as we're looking from Uncle Tom's eye level.

e) A steamroller which takes up most of the frame, as we're looking from Uncle Tom's eye level.He's literally flattened like a piece of paper on the pavement, cartoon-style.

f) An extreme long shot of a PT boat chasing after the swimming Uncle Tom, its huge guns trained right on him. Yet another indication this project began in the closing days of the war. (Or maybe Legree was just able to get Navy surplus...) The boat is, of course, seemingly twice as large as any actual PT boat.

Cut back to the present with Uncle Tom still going, gesturing with his arms as the child on his lap looks increasingly incredulous: "And then them rocket guns, an' them 'bay-zookas'...an' them machine guns, an' them alligators, then all of a sudden..." (The camera pans down toward the child, who shakes his head in pity and disbelief--then the scene fades out.)

(Note: Kevin has since informed me that our skeptical little friend was voiced by veteran radio performer and voice artist Sara Berner.-R.)

When we resume, we see the exterior of an enormous-beyond-enormous skyscraper, which the tiny figures of Legree and Uncle Tom scale like spiders crawling up a wall at about 700 mph.

(V.O: "Then he chase me up that 'Umpire State Building', and pushes me right off the top...") On the words "pushes me right off the top", the scene cuts to another extreme long shot of Legree and Uncle Tom atop the building. It cuts again to another "bird's eye" view, even more impressive

than the first one earlier in the picture, as Uncle Tom rapidly moves away from the viewer toward the ground. This may have been reused in DROOPY'S GOOD DEED, in the scene in which the bulldog, in baby get-up, plummets from the top of a building.

(V.O: "Then I fall down fo'teen miles and hit on the pavement!!") As he says this, we cut to a shot of Uncle Tom hitting the sidewalk with a bounce, arms and legs splayed out. The sidewalk

appears made of rubber, much as in THE CAT THAT HATED PEOPLE.

Here we get perhaps the best line in the picture, and my favorite: "And right there is where I gets mad!!" After all that wild exaggeration, the ultimate Droopy-like understatement.

(V.O. "And I grab up that Umpire State Building with Le-gree up there on top! Then I throws him clean over the moon!") The camera follows the building's flight through the air as it arcs toward the ocean and lands with a splash.

(V.O. "And I grab up that Umpire State Building with Le-gree up there on top! Then I throws him clean over the moon!") The camera follows the building's flight through the air as it arcs toward the ocean and lands with a splash.(Dissolve back to Uncle Tom and child on porch) "And that was the end of Mister Le-gree!" Uncle Tom at this point takes a self-satisfied puff of his cigar.

The child who's been sitting through this snow job the whole time says, "Uncle Tom, are you sure all you been tellin' us is the truth??" Giving the child a momentary scowl, Uncle Tom takes the child off his lap. He says, "Now wait a minute there, boy...(at this point we cut to a shot of him and the rest of the children gathered around him--Uncle Tom points at the child who'd been on his lap) .."if it ain't the truth, I hope that lightnin' come down and strike me dead..."

The cosmos, which apparently has some credibility problems with Uncle Tom's story also,

The cosmos, which apparently has some credibility problems with Uncle Tom's story also,complies. We cut to a shot of storm clouds as a lightning bolt issues forth. The scene again cuts to the bolt of lightning hitting Uncle Tom square in the back, killing him on the spot. A ghost version of him with angel wings and robe (complete with ghostly cigar, no less) rises from his

lifeless body, playing a harp. The camera zooms in on the small child who'd been on Uncle Tom's lap, who delivers the payoff line: "Y'know, we lose more Uncle Toms that way!" With that, we bid farewell to a great storyteller (if not, perhaps, a truthful one) and iris out.

CONCLUDING THOUGHTS

Tex Avery's portrayal of black characters has always been somewhat problematic, prompting some--admittedly, even me at times--to wonder if he was indeed racist. His jungle natives in THE ISLE OF PINGO PONGO at Warner's, and HALF-PINT PYGMY at MGM, are the most extreme caricatures of black people imaginable: pinheaded, with lips that would surely make them too top-heavy to stand. There's also the thorny little matter of his Texas upbringing--surely, some believe, the prejudices of the people around him had to have rubbed off just a little.

Of course, in making that assumption, we're guilty of a bit of prejudice ourselves, in assuming that just because a man comes from an area in which prejudice predominates, he must himself be prejudiced. So did Elvis Presley, and he loved black culture and music--as did Elvis' mentor, Sam Phillips.

Having seen interviews done with Avery toward the end of his life, however, I'm forced to conclude he was incapable of such behavior--he was far too gentle and soft-spoken a man to practice such extreme hatred. Beloved by everyone who had the privilege to know him, there is absolutely no account, anywhere, of him expressing anything close to animosity toward other races.

Though really, if one wishes definitive proof, one need look no further than his cartoons

themselves, especially this one. In some respects it's surprisingly progressive for the era--though still caricatured, Uncle Tom and other black characters aren't the google-eyed, white lipped monstrosities of earlier such cartoons, and are certainly less extreme than those of Clampett's COAL BLACK. Uncle Tom himself could have fit well into a FAT ALBERT cartoon of the seventies, sharing characteristics with that show's character "Mudfoot"--including his tendency to tell wild stories. A credit, certainly, to Preston Blair's Disney-influenced character design in particular.

Further, and even more shocking for the time, Uncle Tom is friends with a white woman--and even goes so far as to express an interest in her--ahem!--attributes: "And that ain't all she got,

neither..." Behavior that would surely have gotten him killed had he been a flesh-and-blood

individual in the South of the day. Even if it all turns out to be Uncle Tom's fantasy, it still

represents a step forward for the time--yet overlooked by just about everyone, critics and fans

alike.

Uncle Tom is also surprisingly human (that is to say, flawed like the rest of us--something that,

incidentally, has nothing to do with race) coming across as a sort of humanoid version of Foghorn Leghorn--with a little bit of Tex Avery himself thrown in, not to mention every grandfather we've ever known. He shares Avery's love of Texas-sized tall tales, giving us a story second only to the previously-mentioned KING SIZE CANARY in its speed and exaggeration. In the scenes in which Uncle Tom goes through a rapidly-escalating series of perils, it might even have surpassed it.

Charles Correll deserved a lot of credit for giving personality to what might have been a

one-dimensional character--though a white man, here was someone with--at the time--nearly

twenty years of radio experience, who know how to make a character come alive through voice

alone. And one who didn't merely say funny things, but say them in a funny way--much like Avery himself. As for the black dialect, it may surprise some people how restrained it is--Uncle Tom says "these," them," there," and "those", not "dese," dem," dere," and "dose." While his grammar isn't perfect, having him speak the King's English perfectly would have been as out of place as it would be with Popeye.

Finally, critics of this cartoon seem to forget that it's a parody, meaning everything--and I do mean everything--is subject to ridicule. Race stereotypes here are presented only to be shot down and given a contemporary spin, as with anything else in Avery's cartoons. In other words, Avery kids the image of black people presented in "Uncle Tom's Cabin," not black people themselves. The same, perhaps, could even be said of his more grotesque caricatures--the blackface gags common to his cartoons, for instance. To his mind, the more extreme something was, the funnier it was--and that included characters as well as actions. Visual exaggeration was his business, almost a mission--and as we've seen, there weren't many who could do it any better.

Tags: Tex+Avery, Uncle+Tom's+Cabana, racial+stereotypes, Charles+Correll, parody, review-synopsis, orphan+toon, MGM, banned